New Harmony, Indiana on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tillich Park Finger Labyrinth

, which was created by Reverend Bill Ressl after an inspirational walk through the park, are also invited to ponder the quotations and discern Tillich's systematic theology.

''The Ends of Utopia''

was created in 2009 by a Vanderbilt University student.

Historic New Harmony

administered by the

''Equitable Commerce'' by Josiah Warren

The ''

Account of the Harmony Society and its beliefs

New Harmony Town Government

{{Authority control Towns in Posey County, Indiana Towns in Indiana Radical Pietism Utopian socialism German-American culture in Indiana Populated places established in 1814 Indiana culture Evansville metropolitan area Communities of Southwestern Indiana Indiana State Historic Sites Christian communities Owenism 1814 establishments in Indiana Territory Intentional communities in the United States

New Harmony is a historic town on the

File:New Harmony Indiana West Street Cabins.JPG, West Street Log Cabins

File:New Harmony Indiana Eigner Cabin.JPG, Eigner Cabin

File:New Harmony Indiana Potter Cabin.JPG, Potter Cabin

''Robert Owen: Pioneer of Social Reforms''

(London: A.C. Fifield, 1908) and that "a plan which remunerates all alike, will, in the present condition of society, ultimately eliminate from a co-operative association the skilled, efficient and industrious members, leaving an ineffective and sluggish residue, in whose hands the experiment will fail, both socially and pecuniarily." However, he still thought that "co-operation ''is'' a chief agency destined to quiet the clamorous conflicts between capital and labour; but then it must be co-operation gradually introduced, prudently managed, as now in England." In 1826 splinter groups dissatisfied with the efforts of the larger community broke away from the main group and prompted a reorganization. In New Harmony work was divided into six departments, each with its own superintendent. These departments included agriculture, manufacturing, domestic economy, general economy, commerce, and literature, science and education. A governing council included the six superintendents and an elected secretary. Despite the new organization and constitution, members continued to leave town. By March 1827, after several other attempts to reorganize, the utopian experiment had failed. The larger community, which lasted until 1827, was divided into smaller communities that led further disputes. Individualism replaced socialism in 1828 and New Harmony was dissolved in 1829 due to constant quarrels. The town's parcels of land and property were returned to private use. Owen spent $200,000 of his own funds to purchase New Harmony property and pay off the community's debts. His sons, Robert Dale and William, gave up their shares of the New Lanark mills in exchange for shares in New Harmony. Later, Owen "conveyed the entire New Harmony property to his sons in return for an annuity of $1,500 for the remainder of his life." Owen left New Harmony in June 1827 and focused his interests in the United Kingdom. He died in 1858.

"David Dale Owen and Joseph Granville Norwood: Pioneer Geologists in Indiana and Illinois"

''Indiana Magazine of History'' 92, no. 1 (March 1996): 15. Retrieved 2012-6-19. Among Owen's most significant publications is his ''Report of a Geological Survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota and Incidentally of a Portion of Nebraska Territory'' (Philadelphia, 1852). Several men trained Owen's leadership and influence:

"New Harmony Collection, 1814–1884" collection guide

Retrieved 2012-7-25. He assisted his brother, David Dale Owen, with geological survey and became Indiana's second state geologist. During the American Civil War, Colonel Richard Owen was commandant in charge of Confederate prisoners at Camp Morton in Indianapolis.Wilson, p. 200. Following his retirement from the U.S. Army in 1864, Owen became a professor of natural sciences at

Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World

' (1860), aroused something of a literary sensation. Among his critics in the ''Boston Investigator'' and at home in the ''New Harmony Advertiser'' were John and

"Frances Wright"

University of Evansville. Retrieved 2012-6-20. Wright married William Philquepal d'Arusmont, a Pestalozzian educator she met at New Harmony. The couple also lived in

"Francis Joseph Nicholas Neef"

University of Evansville. Retrieved 2012-6-20. Maclure brought Neef, a Pestalozzian educator from Switzerland, to Philadelphia, and placed him in charge of his school for boys. It was the first school in the United States to be based on Pestalozzian methods. In 1826 Neef, his wife, and children came to New Harmony to run the schools under Maclure's direction.Wilson, p. 185. Neef, following Maclure's curriculum, became superintendent of the schools in New Harmony, where as many as 200 students, ranging in age from five to twelve, were enrolled.

(c. 1763–1863) lived in New Harmony from 1836 until his death. During this time he prolifically painted portraiture in the ''fraktur'' style and portrayed the dress and décor of local Owenites. Examples of his work are displayed in the Wabash River

The Wabash River ( French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows fro ...

in Harmony Township, Posey County

Posey may refer to:

Places

* Posey, California

* Posey, Illinois

* Posey, Texas

* Posey, West Virginia

* Posey County, Indiana

* Posey Township, Indiana (disambiguation)

People

* Posey (Paiute) (1860s–1923), Paiute chief

* Posey (surnam ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

. It lies north of Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on ...

, the county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US st ...

, and is part of the Evansville metropolitan area

The Evansville metropolitan area is the 164th largest metropolitan statistical area (MSA) in the United States. The primary city is Evansville, Indiana, the third largest city in Indiana and the largest city in Southern Indiana as well as the h ...

. The town's population was 789 at the 2010 census.

Established by the Harmony Society

The Harmony Society was a Christian theosophy and pietist society founded in Iptingen, Germany, in . Due to religious persecution by the Lutheran Church and the government in Württemberg, the group moved to the United States,Robert Paul Sutto ...

in 1814 under the leadership of George Rapp

John George Rapp (german: Johann Georg Rapp; November 1, 1757 in Iptingen, Duchy of Württemberg – August 7, 1847 in Economy, Pennsylvania) was the founder of the religious sect called Harmonists, Harmonites, Rappites, or the Harmony Society ...

, the town was originally known as Harmony (also called Harmonie, or New Harmony). In its early years the settlement was the home of Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

s who had separated from the official church in the Duchy of Württemberg

The Duchy of Württemberg (german: Herzogtum Württemberg) was a duchy located in the south-western part of the Holy Roman Empire. It was a member of the Holy Roman Empire from 1495 to 1806. The dukedom's long survival for over three centuries ...

and immigrated to the United States. The Harmonists built a new town in the wilderness, but in 1824 they decided to sell their property and return to Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted e ...

, a Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

industrialist and social reformer, purchased the town in 1825 with the intention of creating a new utopian community

An intentional community is a voluntary residential community which is designed to have a high degree of social cohesion and teamwork from the start. The members of an intentional community typically hold a common social, political, religious, ...

and renamed it New Harmony. The Owenite

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

social experiment

A social experiment is a type of Psychology, psychological or Sociology, sociological research for testing people's reactions to certain situations or events. The experiment depends on a particular social approach where the main source of inform ...

failed two years after it began.Ray E. Boomhower, "New Harmony: Home to Indiana's Communal Societies," ''Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History'' 14(4):36–37.

New Harmony changed American education and scientific research. Town residents established the first public library, a civic drama club, and a public school system open to men and women. Its prominent citizens included Owen's sons: Robert Dale Owen

Robert Dale Owen (7 November 1801 – 24 June 1877) was a Scottish-born Welsh social reformer who immigrated to the United States in 1825, became a U.S. citizen, and was active in Indiana politics as member of the Democratic Party in the Ind ...

, an Indiana congressman and social reformer who sponsored legislation to create the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

; David Dale Owen

David Dale Owen (24 June 1807 – 13 November 1860) was a prominent American geologist who conducted the first geological surveys of Indiana, Kentucky, Arkansas, Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota. Owen served as the first state geologist for three sta ...

, a noted state and federal geologist; William Owen, a New Harmony businessman; and Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

, Indiana state geologist, Indiana University professor, and first president of Purdue University

Purdue University is a public land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded in 1869 after Lafayette businessman John Purdue donated land and money ...

. The town also served as the second headquarters of the U.S. Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, and ...

. Numerous scientists and educators contributed to New Harmony's intellectual community, including William Maclure

William Maclure (27 October 176323 March 1840) was an Americanized Scottish geologist, cartographer and philanthropist. He is known as the 'father of American geology'. As a social experimenter on new types of community life, he collaborated ...

, Marie Louise Duclos Fretageot

Marie may refer to:

People Name

* Marie (given name)

* Marie (Japanese given name)

* Marie (murder victim), girl who was killed in Florida after being pushed in front of a moving vehicle in 1973

* Marie (died 1759), an enslaved Cree person in T ...

, Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and Herpetology, herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Ge ...

, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, Joseph Neef

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, Frances Wright

Frances Wright (September 6, 1795 – December 13, 1852), widely known as Fanny Wright, was a Scottish-born lecturer, writer, freethinker, feminist, utopian socialist, abolitionist, social reformer, and Epicurean philosopher, who became a ...

, and others.

Many of the town's old Harmonist buildings have been restored. These structures, along with others related to the Owenite community, are included in the New Harmony Historic District

The New Harmony Historic District is a National Historic Landmark District in New Harmony, Indiana. It received its landmark designation in 1965, and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, with a boundary increase in 20 ...

. Contemporary additions to the town include the Roofless Church

The Roofless Church in New Harmony, Indiana, is an open air interdenominational church designed by Philip Johnson and dedicated in 1960. The church was commissioned by Jane Blaffer Owen, the wife of a descendant of Robert Owen (the founder of Ne ...

and Atheneum. The New Harmony State Memorial is located south of town on State Road 69 in Harmonie State Park

Harmonie is a state park in Indiana. It is located in Posey County, Indiana, about northwest of Evansville, Indiana

Evansville is a city in, and the county seat of, Vanderburgh County, Indiana, United States. The population was 118,414 at ...

.

History

Harmonist settlement (1814–1824)

The town of Harmony was founded by theHarmony Society

The Harmony Society was a Christian theosophy and pietist society founded in Iptingen, Germany, in . Due to religious persecution by the Lutheran Church and the government in Württemberg, the group moved to the United States,Robert Paul Sutto ...

in 1814 under the leadership of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

immigrant George Rapp

John George Rapp (german: Johann Georg Rapp; November 1, 1757 in Iptingen, Duchy of Württemberg – August 7, 1847 in Economy, Pennsylvania) was the founder of the religious sect called Harmonists, Harmonites, Rappites, or the Harmony Society ...

(born Johann Georg Rapp). It was the second of three towns built by the pietist

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life, including a social concern for ...

, communal religious group, known as Harmonists, Harmonites, or Rappites. The Harmonists settled in the Indiana Territory

The Indiana Territory, officially the Territory of Indiana, was created by a United States Congress, congressional act that President of the United States, President John Adams signed into law on May 7, 1800, to form an Historic regions of the U ...

after leaving Harmony, Pennsylvania

Harmony is a borough in Butler County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 890 at the 2010 census. It is located approximately north of Pittsburgh.

Geography

Harmony is located in southwestern Butler County, along the northeastern ...

, where westward expansion, the area's rising population, jealous neighbors, and the increasing cost of land threatened the Society's desire for isolation.

In April 1814 Anna Mayrisch, John L. Baker, and Ludwick Shirver (Ludwig Schreiber) traveled west in search of a new location for their congregation, one that would have fertile soil and access to a navigable waterway. By May 10 the men had found suitable land along the Wabash River in the Indiana Territory and made an initial purchase of approximately . Rapp wrote on May10, "The place is 25 miles from the Ohio mouth of the Wabash, and 12 miles from where the Ohio makes its curve first before the mouth. The town will be located about 1/4 mile from the river above on the channel on a plane as level as the floor of a room, perhaps a good quarter mile from the hill which lies suitable for a vineyard."Arndt, ''A Documentary History of the Indiana Decade of the Harmony Society'', 1:8. Although Rapp expressed concern that the town's location lacked a waterworks, the area provided an opportunity for expansion and access to markets through the nearby rivers, causing him to remark, "In short, the place has all the advantages which one could wish, if a steam engine meanwhile supplies what is lacking."

The first Harmonists left Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

in June 1814 and traveled by flatboat to their new land in the Indiana Territory. In May 1815 the last of the Harmonists who had remained behind until the sale of their town in Pennsylvania was completed departed for their new town along the Wabash River. Frederick Reichert Rapp, George Rapp's adopted son, drew up the town plan for their new village at Harmony, Indiana

Harmony is a town in Van Buren Township, Clay County, Indiana, United States. The population was 656 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Terre Haute Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Harmony was platted in 1864, although there had long b ...

, which surveyors laid out on August8, 1814. By 1816, the same year that Indiana became a state, the Harmonists had acquired of land, built 160 homes and other buildings, and cleared for their new town. The settlement also began to attract new arrivals, including emigrants from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

such as members of Rapp's congregation from Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Würt ...

, many of whom expected the Harmonists to pay for their passage to America. However, the new arrivals "were more of a liability than an asset".Arndt, ''George Rapp's Harmony Society'', p. 209. On March 20, 1819, Rapp commented, "It is astonishing how much trouble the people who have arrived here have made, for they have no morals and do not know what it means to live a moral and well-mannered life, not to speak of true Christianity, of denying the world or yourself."

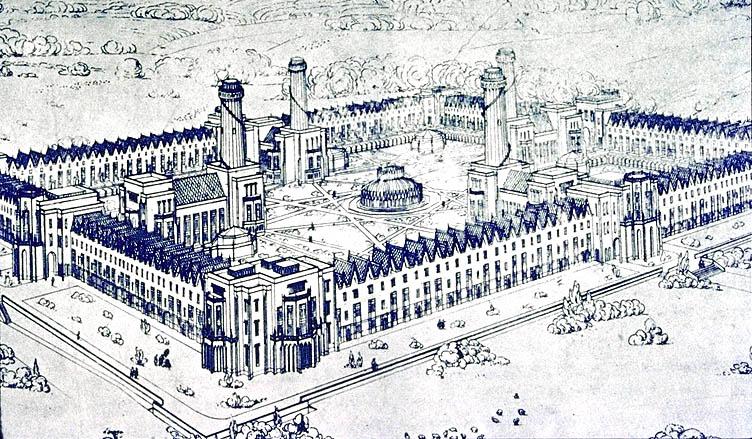

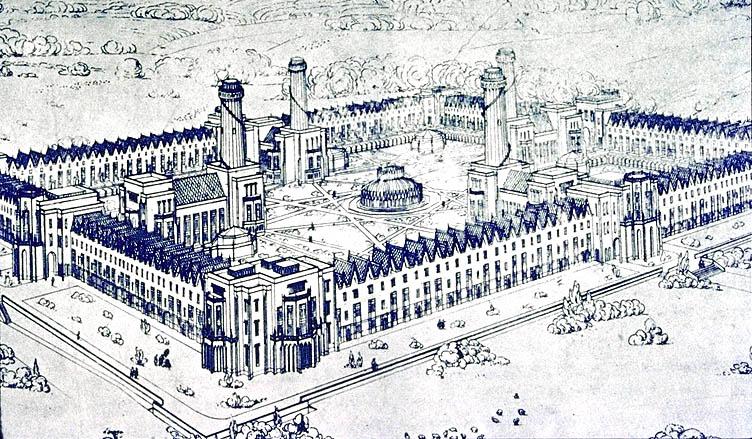

Visitors to Harmony commented on the commercial and industrial work being done in this religious settlement along the Wabash River. "It seemed as though I found myself in the midst of Germany," noted one visitor.Arndt, ''A Documentary History of the Indiana Decade of the Harmony Society'', 1:744. In 1819 the town had a steam-operated wool carding and spinning factory, a horse-drawn and human-powered threshing machine, a brewery, distillery, vineyards, and a winery. The property included an orderly town, "laid out in a square", with a church, school, store, dwellings for residents, and streets to create "the most beautiful city of western America, because everything is built in the most perfect symmetry". Other visitors were not as impressed: "hard labor & coarse fare appears to be the lot of all except the family of Rapp, he lives in a large & handsome brick house while the rest inhabit small log cabins. How so numerous a population are kept quietly & tamely in absolute servitude it is hard to conceive—the women I believe do more labor in the field than the men, as large numbers of the latter are engaged in different branches of manufactures." Although they were not paid for their work, the 1820 manufacturer's census reported that 75 men, 12 women, and 30 children were employed, in the Society's tanneries, saw and grain mills, and woolen and cotton mills. Manufactured goods included cotton, flannel, and wool cloth, yarn, knit goods, tin ware, rope, beer, peach brandy, whiskey, wine, wagons, carts, plows, flour, beef, pork, butter, leather, and leather goods.

The Harmonist community continued to thrive during the 1820s, but correspondence from March 6, 1824, between Rapp and his adopted son, Frederick, indicates that the Harmonists planned to sell their Indiana property and were already looking for a new location. In May, a decade after their arrival in Indiana, the Harmonists purchased land along the Ohio River eighteen miles from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, and were making arrangements to advertise the sale of their property in Indiana. The move, although it was made primarily for religious reasons, would provide the Harmonists with easier access to eastern markets and a place where they could live more peacefully with others who shared their German language and culture. On May 24, 1824, a group of Harmonists boarded a steamboat and departed Indiana, bound for Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, where they founded the community of Economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

, the present-day town of Ambridge. In May 1825 the last Harmonists left Indiana after the sale of their of property, which included the land and buildings, to Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted e ...

for $150,000.Boomhower, p. 37. Owen hoped to establish a new community on the Indiana frontier, one that would serve as a model community for communal living and social reform.

Owenite community (1825–1827)

Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted e ...

was a social reformer and wealthy industrialist who made his fortune from textile mills in New Lanark

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometres) from Lanark, in Lanarkshire, and some southeast of Glasgow, Scotland. It was founded in 1785 and opened in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and housi ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

. Owen, his twenty-two-year-old son, William, and his Scottish friend Donald McDonald sailed to the United States in 1824 to purchase a site to implement Owen's vision for "a New Moral World" of happiness, enlightenment, and prosperity through education, science, technology, and communal living. Owen believed his utopian community would create a "superior social, intellectual and physical environment" based on his ideals of social reform.Donald E. Pitzer, "The Original Boatload of Knowledge Down the Ohio River." Reprint. ''Ohio Journal of Science'' 89, no. 5 (December 1989):128–142. Owen was motivated to buy the town in order to prove his theories were viable and to correct the troubles that were affecting his mill-town community New Lanark

New Lanark is a village on the River Clyde, approximately 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometres) from Lanark, in Lanarkshire, and some southeast of Glasgow, Scotland. It was founded in 1785 and opened in 1786 by David Dale, who built cotton mills and housi ...

. The ready-built town of Harmony, Indiana, fitted Owen's needs. In January 1825 he signed the agreement to purchase the town, renamed it New Harmony, and invited "any and all" to join him there. While many of the town's new arrivals had a sincere interest in making it a success, the experiment also attracted "crackpots, free-loaders, and adventurers whose presence in the town made success unlikely." William Owen, who remained in New Harmony while his father returned east to recruit new residents, also expressed concern in his diary entry, dated March24, 1825: "I doubt whether those who have been comfortable and content in their old mode of life, will find an increase of enjoyment when they come here. How long it will require to accustom themselves to their new mode of living, I am unable to determine."

When Robert Owen returned to New Harmony in April 1825 he found seven hundred to eight hundred residents and a "chaotic" situation, much in need of leadership. By May 1825 the community had adopted the "Constitution of the Preliminary Society," which loosely outlined its expectations and government. Under the preliminary constitution, members would provide their own household goods and invest their capital at interest in an enterprise that would promote independence and social equality. Members would render services to the community in exchange for credit at the town's store, but those who did not want to work could purchase credit at the store with cash payments made in advance. In addition, the town would be governed by a committee of four members chosen by Owen and the community would elect three additional members. In June, Robert Owen left William in New Harmony while he traveled east to continue promoting his model community and returned to Scotland, where he sold his interests in the New Lanark textile mills and arranged financial support for his wife and two daughters, who chose to remain in Scotland. Owen's four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale, and Richard, and a daughter, Jane Dale, later settled in New Harmony.

While Owen was away recruiting new residents for New Harmony, a number of factors that led to an early breakup of the socialist community

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

had already begun. Members grumbled about inequity in credits between workers and non-workers. In addition, the town soon became overcrowded, lacked sufficient housing, and was unable to produce enough to become self-sufficient, although they still had "high hopes for the future." Owen spent only a few months at New Harmony, where a shortage of skilled craftsmen and laborers along with inadequate and inexperienced supervision and management contributed to its eventual failure.

Despite the community's shortcomings, Owen was a passionate promoter of his vision for New Harmony. While visiting Philadelphia, Owen met Marie Louise Duclos Fretageot

Marie may refer to:

People Name

* Marie (given name)

* Marie (Japanese given name)

* Marie (murder victim), girl who was killed in Florida after being pushed in front of a moving vehicle in 1973

* Marie (died 1759), an enslaved Cree person in T ...

, a Pestalozzian

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (, ; 12 January 1746 – 17 February 1827) was a Swiss pedagogue and educational reformer who exemplified Romanticism in his approach.

He founded several educational institutions both in German- and French-speaking r ...

educator, and persuaded her to join him in Indiana. Fretageot encouraged William Maclure

William Maclure (27 October 176323 March 1840) was an Americanized Scottish geologist, cartographer and philanthropist. He is known as the 'father of American geology'. As a social experimenter on new types of community life, he collaborated ...

, a scientist and fellow educator, to become a part of the venture. (Maclure became Owen's financial partner.) On January 26, 1826, Fretegeot, Maclure, and a number of their colleagues, including Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and Herpetology, herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Ge ...

, Josef Neef Josef may refer to

*Josef (given name)

*Josef (surname)

* ''Josef'' (film), a 2011 Croatian war film

*Musik Josef

Musik Josef is a Japanese manufacturer of musical instruments. It was founded by Yukio Nakamura, and is the only company in Japan spe ...

, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, and others aboard the keelboat ''Philanthropist'' (also called the "Boatload of Knowledge"), arrived in New Harmony to help Owen establish his new experiment in socialism.

On February 5, 1826, the town adopted a new constitution, "The New Harmony Community of Equality", whose objective was to achieve happiness based on principles of equal rights and equality of duties. Cooperation, common property, economic benefit, freedom of speech and action, kindness and courtesy, order, preservation of health, acquisition of knowledge, and obedience to the country's laws were included as part of the constitution. The constitution laid out the life of a citizen in New Harmony based on age. Children from the age of one to five were to be cared for and encouraged to exercise; children aged six to nine they were to be lightly employed and given education via observation directed by skilled teachers. Youth from the ages of ten to twelve were to help in the houses and with the gardening. Teenagers from the age of twelve to fifteen were to receive technical training, and from fifteen to twenty their education was to be continued. Young adults from the ages of twenty to thirty were to act as a superintendent in the production and education departments. Adults from the ages of thirty to forty were to govern the homes, and residents aged forty to sixty were to be encouraged to assist with the community's external relations or to travel abroad if they so desired.

Although the constitution contained worthy ideals, it did not clearly address how the community would function and was never fully established. Individualist anarchist

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

, who was one of the original participants in the New Harmony Society, asserted that the community was doomed to failure due to a lack of individual sovereignty and private property. He commented: "It seemed that the difference of opinion, tastes and purposes increased just in proportion to the demand for conformity. Two years were worn out in this way; at the end of which, I believe that not more than three persons had the least hope of success. Most of the experimenters left in despair of all reforms, and conservatism felt itself confirmed. We had tried every conceivable form of organization and government. We had a world in miniature. --we had enacted the French revolution over again with despairing hearts instead of corpses as a result. ...It appeared that it was nature's own inherent law of diversity that had conquered us ...our 'united interests' were directly at war with the individualities of persons and circumstances and the instinct of self-preservation... and it was evident that just in proportion to the contact of persons or interests, so are concessions and compromises indispensable." (''Periodical Letter II'' 1856).

Part of New Harmony's failings stemmed from three activities that Owen brought from Scotland to America. First, Owen actively attacked established religion, despite United States' constitutional guarantees of religious freedom and the separations of church and state. Second, Owen remained stubbornly attached to the principles of the rationalist Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, which drove away many of the Jeffersonian farmers Owen tried to attract. Thirdly, Owen consistently appealed to the upper class for donations, but found that the strategy was not as effective as it had been in Europe.

Robert Dale Owen wrote that the members of the failed socialist experiment at New Harmony were "a heterogeneous collection of radicals, enthusiastic devotees to principle, honest latitudinarian

Latitudinarians, or latitude men, were initially a group of 17th-century English theologiansclerics and academicsfrom the University of Cambridge who were moderate Anglicans (members of the Church of England). In particular, they believed that ...

s, and lazy theorists, with a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in,"Joseph Clayton''Robert Owen: Pioneer of Social Reforms''

(London: A.C. Fifield, 1908) and that "a plan which remunerates all alike, will, in the present condition of society, ultimately eliminate from a co-operative association the skilled, efficient and industrious members, leaving an ineffective and sluggish residue, in whose hands the experiment will fail, both socially and pecuniarily." However, he still thought that "co-operation ''is'' a chief agency destined to quiet the clamorous conflicts between capital and labour; but then it must be co-operation gradually introduced, prudently managed, as now in England." In 1826 splinter groups dissatisfied with the efforts of the larger community broke away from the main group and prompted a reorganization. In New Harmony work was divided into six departments, each with its own superintendent. These departments included agriculture, manufacturing, domestic economy, general economy, commerce, and literature, science and education. A governing council included the six superintendents and an elected secretary. Despite the new organization and constitution, members continued to leave town. By March 1827, after several other attempts to reorganize, the utopian experiment had failed. The larger community, which lasted until 1827, was divided into smaller communities that led further disputes. Individualism replaced socialism in 1828 and New Harmony was dissolved in 1829 due to constant quarrels. The town's parcels of land and property were returned to private use. Owen spent $200,000 of his own funds to purchase New Harmony property and pay off the community's debts. His sons, Robert Dale and William, gave up their shares of the New Lanark mills in exchange for shares in New Harmony. Later, Owen "conveyed the entire New Harmony property to his sons in return for an annuity of $1,500 for the remainder of his life." Owen left New Harmony in June 1827 and focused his interests in the United Kingdom. He died in 1858.

Accomplishments

Science

Although Robert Owen's vision of New Harmony as an advance in social reform was not realized, the town became a scientific center of national significance, especially in the natural sciences, most notably geology.William Maclure

William Maclure (27 October 176323 March 1840) was an Americanized Scottish geologist, cartographer and philanthropist. He is known as the 'father of American geology'. As a social experimenter on new types of community life, he collaborated ...

(1763–1840), president of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the Americas. It was founded in 1812, by many of the leading nat ...

from 1817 to 1840, came to New Harmony during the winter of 1825–1826. Maclure brought a group of noted artists, educators, and fellow scientists, including naturalists Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and Herpetology, herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Ge ...

and Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, to New Harmony from Philadelphia aboard the keelboat

A keelboat is a riverine cargo-capable working boat, or a small- to mid-sized recreational sailing yacht. The boats in the first category have shallow structural keels, and are nearly flat-bottomed and often used leeboards if forced in open wat ...

''Philanthropist'' (also known as the "Boatload of Knowledge").

Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and Herpetology, herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Ge ...

(1787–1834), a friend of Maclure, was an entomologist and conchologist. His definitive studies of shells and insects, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, and elsewhere made him an internationally known naturalist. Say has been called the father of American descriptive entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

and American conchology

Conchology () is the study of mollusc shells. Conchology is one aspect of malacology, the study of molluscs; however, malacology is the study of molluscs as whole organisms, whereas conchology is confined to the study of their shells. It includ ...

. Prior to his arrival at New Harmony, he served as librarian for the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, curator at the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

, and professor of natural history at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

. Say died in New Harmony in 1834.Wilson, p. 184.

Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1778–1846), a naturalist and artist, came to New Harmony aboard the ''Philanthropist''. His sketches of New Harmony provide a visual record of the town during the Owenite period. As a naturalist, Lesueur is known for his classification of Great Lakes fishes. He returned to his native France in 1837. Many species were first described by both Say and Leseuer, and many have been named in their honor.

David Dale Owen

David Dale Owen (24 June 1807 – 13 November 1860) was a prominent American geologist who conducted the first geological surveys of Indiana, Kentucky, Arkansas, Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota. Owen served as the first state geologist for three sta ...

(1807–1860), third son of Robert Owen, finished his formal education as a medical doctor in 1837. However, after returning to New Harmony, David Dale Owen was influenced by the work of Maclure and Gerard Troost

Gerardus Troost (March 5, 1776 – August 14, 1850) was a Dutch-American medical doctor, naturalist, mineralogist, and founding member and first president of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences.; archive.org copie

Biography

Troost was ...

, a Dutch geologist, mineralogist, zoologist, and chemist who arrived in New Harmony in 1825 and later became the state geologist of Tennessee from 1831 to 1850. Owen went on to become a noted geologist. Headquartered at New Harmony, Owen conducted the first official geological survey of Indiana (1837–39). After his appointment as U.S. Geologist in 1839, Owen led federal surveys from 1839 to 1840 and from 1847 to 1851 of the Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

, which included Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

, and part of northern Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

. In 1846 Owen sampled a number of possible building stones for the Smithsonian Institution Building

The Smithsonian Institution Building, located near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. behind the National Museum of African Art and the Sackler Gallery, houses the Smithsonian Institution's administrative offices and information center. The ...

(the Smithsonian "Castle") and recommended the distinctive Seneca Creek sandstone of which that building is constructed. The following year, Owen identified a quarry at Bull Run, twenty-three miles from nation's capital, that provided the stone for the massive building. Owen became the first state geologist of three states: Kentucky (1854–1857), Arkansas (1857–1859), and Indiana (1837–1839 and 1859–1860). Owen's museum and laboratory in New Harmony was known as the largest west of the Allegheny Mountains. At the time of Owen's death in 1860, his museum included some 85,000 items.Clark Kimberling"David Dale Owen and Joseph Granville Norwood: Pioneer Geologists in Indiana and Illinois"

''Indiana Magazine of History'' 92, no. 1 (March 1996): 15. Retrieved 2012-6-19. Among Owen's most significant publications is his ''Report of a Geological Survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota and Incidentally of a Portion of Nebraska Territory'' (Philadelphia, 1852). Several men trained Owen's leadership and influence:

Benjamin Franklin Shumard

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's thir ...

, for whom the Shumard oak is named, was appointed state geologist of Texas by Governor Hardin R. Runnels; Amos Henry Worthen

Amos Henry Worthen (1813–1888) was an American geologist and paleontologist from Illinois. He was the second state geologist of Illinois and the first curator of the Illinois State Museum. He was a fellow of the American Association for the Ad ...

was the second state geologist of Illinois and the first curator of the Illinois State Museum; and Fielding Bradford Meek

Fielding Bradford Meek (December 10, 1817 – December 22, 1876) was an American geologist and a paleontologist who specialized in the invertebrates.

Biography

The son of a lawyer, he was born in Madison, Indiana. In early life he was in bu ...

became the first full-time paleontologist in lieu of salary at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. Joseph Granville Norwood

Joseph Granville Norwood (December 20, 1807 – May 6, 1895) was a medical doctor and scientist who served in a variety of government capacities in the geological exploration of the upper Midwest, and finished his career as a professor of med ...

, one of David Dale Owen's colleagues and coauthors, also a medical doctor, became the first state geologist of Illinois (1851–1858). From 1851 to 1854, the Illinois State Geological Survey was headquartered in New Harmony.

Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

(1810–1890), Robert Owen's youngest son, came to New Harmony in 1828 and initially taught school there.Indiana Historical Society

The Indiana Historical Society (IHS) is one of the United States' oldest and largest historical societies and describes itself as "Indiana's Storyteller". It is housed in the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Indiana History Center at 450 West Ohio Street ...

"New Harmony Collection, 1814–1884" collection guide

Retrieved 2012-7-25. He assisted his brother, David Dale Owen, with geological survey and became Indiana's second state geologist. During the American Civil War, Colonel Richard Owen was commandant in charge of Confederate prisoners at Camp Morton in Indianapolis.Wilson, p. 200. Following his retirement from the U.S. Army in 1864, Owen became a professor of natural sciences at

Indiana University

Indiana University (IU) is a system of public universities in the U.S. state of Indiana.

Campuses

Indiana University has two core campuses, five regional campuses, and two regional centers under the administration of IUPUI.

*Indiana Universit ...

in Bloomington, where an academic building is named in his honor. In 1872 Owen became the first president of Purdue University

Purdue University is a public land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded in 1869 after Lafayette businessman John Purdue donated land and money ...

, but resigned from this position in 1874. He continued teaching at IU until his retirement in 1879.

Public service and social reform

Robert Dale Owen

Robert Dale Owen (7 November 1801 – 24 June 1877) was a Scottish-born Welsh social reformer who immigrated to the United States in 1825, became a U.S. citizen, and was active in Indiana politics as member of the Democratic Party in the Ind ...

, eldest son of Robert Owen, was a social reformer and intellectual of national importance. At New Harmony, he taught school and co-edited and published the ''New Harmony Gazette'' with Frances Wright.Walker, p . 23. Owen later moved to New York. In 1830 he published "Moral Philosophy," the first treatise in the United States to support birth control, and returned to New Harmony in 1834. From 1836 to 1838, and in 1851, Owen served in the Indiana legislature and was also a delegate to the state's constitutional convention of 1850. Owen was an advocate for women's rights, free public education, and opposed slavery. As a member of the U. S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from 1843 to 1847, Owen introduced a bill in 1846 that established the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. He also served as chairman of the Smithsonian Building Committee. He arranged for his brother, David Dale Owen, to sample a large number of possible building stones for the Smithsonian Castle. From 1852 to 1858 Owen held the diplomatic position of charge d'affairs (1853–1858) in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, where he began studying spiritualism.Wilson, p. 196–197. Owen's book, Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World

' (1860), aroused something of a literary sensation. Among his critics in the ''Boston Investigator'' and at home in the ''New Harmony Advertiser'' were John and

Margaret Chappellsmith

Margaret Chappellsmith (1806–1883) was a socialist lecturer, active in London, England and the United States of America in the 19th Century. She campaigned on communitarianism, currency reform and the women's position.

Early life

Chappellsmi ...

, he formerly an artist for David Dale Owen's geological publications, and she a former Owenite lecturer. Robert Dales Owen died at Lake George, New York, in 1877.

Frances Wright

Frances Wright (September 6, 1795 – December 13, 1852), widely known as Fanny Wright, was a Scottish-born lecturer, writer, freethinker, feminist, utopian socialist, abolitionist, social reformer, and Epicurean philosopher, who became a ...

(1795–1852) came to New Harmony in 1824, where she co-edited and wrote for the ''New Harmony Gazette'' with Robert Dale Owen. In 1825 she established an experimental settlement at Nashoba, Tennessee, that allowed African American slaves to work to gain their freedom, but the community failed. A liberal leader in the "free-thought movement," Wright opposed slavery, advocated woman's suffrage, birth control, and free public education. Wright and Robert Dale Owen moved their newspaper to New York City in 1829 and published it as the ''Free Enquirer''.Clark Kimberling"Frances Wright"

University of Evansville. Retrieved 2012-6-20. Wright married William Philquepal d'Arusmont, a Pestalozzian educator she met at New Harmony. The couple also lived in

Paris, France

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, and in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, where they divorced in 1850. Wright died in Cincinnati in 1852.

Education

The history of education at New Harmony involves several teachers who were already well-established in their fields before they moved to New Harmony, largely through the efforts of William Maclure. These Pestalozzian educators included Marie Duclos Fretageot and Joseph Neef. By the time Maclure arrived in New Harmony he had already established the first Pestalozzian school in America. Fretageot and Neef had been Pestalozzian educators and school administrators at Maclure's schools in Pennsylvania. Under Maclure's direction and using his philosophy of education, New Harmony schools became the first public schools in the United States open to boys and girls. Maclure also established at New Harmony one of the country's first industrial or trade schools. He also had his extensive library and geological collection shipped to New Harmony from Philadelphia. In 1838 Maclure established The Working Men's Institute, a society for "mutual instruction". It includes the oldest continuously operating library in Indiana, as well as a small museum. The vault in the library contains many historic manuscripts, letters, and documents pertaining to the history of New Harmony. Under the terms of his will, Maclure also offered $500 to any club or society of laborers in the United States who established a reading and lecture room with a library of at least 100 books. About 160 libraries in Indiana and Illinois took advantage of his bequest. Marie Duclos Fretageot managed Pestalozzian schools that Maclure organized in France and Philadelphia before coming to New Harmony aboard the ''Philanthropist''. In New Harmony she was responsible for the infant's school (for children under age five), supervised several young women she had brought with her from Philadelphia, ran a store, and was Maclure's administrator during his residence in Mexico. Fretageot remained in New Harmony until 1831, returned to France, and later joined Maclure in Mexico, where she died in 1833. Correspondence of Maclure and Fretageot from 1820 to 1833 was extensive and is documented in ''Partnership for Posterity.''Joseph Neef

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

( 1770–1854) published in 1808 the first work on educational method to be written in English in the United States, ''Sketch of A Plan and Method of Education.''Clark Kimberling"Francis Joseph Nicholas Neef"

University of Evansville. Retrieved 2012-6-20. Maclure brought Neef, a Pestalozzian educator from Switzerland, to Philadelphia, and placed him in charge of his school for boys. It was the first school in the United States to be based on Pestalozzian methods. In 1826 Neef, his wife, and children came to New Harmony to run the schools under Maclure's direction.Wilson, p. 185. Neef, following Maclure's curriculum, became superintendent of the schools in New Harmony, where as many as 200 students, ranging in age from five to twelve, were enrolled.

Jane Dale Owen Fauntleroy

Jane may refer to:

* Jane (given name), a feminine given name

* Jane (surname), related to the given name

Film and television

* ''Jane'' (1915 film), a silent comedy film directed by Frank Lloyd

* ''Jane'' (2016 film), a South Korean drama fi ...

(1806–1861), daughter of Robert Owen, arrived in New Harmony in 1833. She married civil engineer Robert Henry Fauntleroy in 1835. He became a business partner of David Dale and Robert Dale Owen. Jane Owen Fauntleroy established a seminary for young women in her family's New Harmony home, where her brother, David Dale Owen, taught science.

Students in New Harmony now attend North Posey High School

North Posey Senior High School is a public high school located in Poseyville, Indiana. North Posey is the high school for the MSD of North Posey County, which includes Bethel, Robb, Smith, Harmony, Center and Robinson Townships in Posey County, ...

after New Harmony High School closed in 2012.

Publishing

Cornelius Tiebout Cornelius Tiebout (1773?-1832) was an American Intaglio (printmaking), copperplate engraver. According to the Library of Congress and many followers, Tiebout was born about 1773. If so, his earliest known engraving was published while he was about f ...

(c. 1773–1832) was an artist, printer, and engraver of considerable fame when he joined the New Harmony community in September 1826. Tiebout taught printing and published a bimonthly newspaper, ''Disseminator of Useful Knowledge'', and books using the town's printing press. He died in New Harmony in 1832.

Publications from New Harmony's press include William Maclure's ''Essay on the Formation of Rocks, or an Inquiry into the Probably Origin of their Present Form'' (1832); and Maclure's ''Structure'' and ''Observations on the Geology of the West India Islands; from Barbadoes to Santa Cruz, Inclusive'' (1832); Thomas Say's ''Description of New Species of North American Insects; Observations on Some of the Species Already Described''; ''Descriptions of Some New Terrestrial and Fluviatile Shells of North America''; and several of the early volumes of Say's ''American Conchology, or Descriptions of the Shells of North America''. (The seventh volume of ''American Conchology'' was published in Philadelphia.)

Lucy Sistare Say was an apprentice at Fretageot's Pestalozzian school and a former student of Lesueur in Philadelphia before coming to New Harmony aboard the ''Philanthropist'' to teach needlework and drawing. En route to Indiana, Sistare met Thomas Say and the two were married on January 4, 1827, prior to their arrival at New Harmony. An accomplished artist, Say illustrated and hand-colored 66 of the 68 illustrations in ''American Conchology,'' her husband's multi-volume work on mollusks. Following Thomas Say's death in 1834, she moved to New York, trained to become an engraver, and worked to complete and publish the final volume of ''American Conchology''. Lucy Say remained interested in the natural sciences after returning to the East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

. In 1841 she became the first female member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.Jacob Maentel

Jacob Maentel or Mental (1763–1863) was a German-American folk artist known for his portrayal of 19th-Century America. Maentel is most notable for his watercolor portrait art that minutely portrayed the décor and dress of early American immigr ...Smithsonian American Art Museum

The Smithsonian American Art Museum (commonly known as SAAM, and formerly the National Museum of American Art) is a museum in Washington, D.C., part of the Smithsonian Institution. Together with its branch museum, the Renwick Gallery, SAAM holds o ...

, the American Folk Art Museum

The American Folk Art Museum is an art museum in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, at 2, Lincoln Square, Columbus Avenue at 66th Street. It is the premier institution devoted to the aesthetic appreciation of folk art and creative expressions of ...

, and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Museum.

Publications on the history of New Harmony include the work of the New Harmony historian and resident, Josephine Mirabella Elliott.

Theater

William Owen (1802–1842), Robert Owen's second oldest son, was involved in New Harmony's business and community affairs. He was among the leaders who founded New Harmony's Thespian Society and acted in some of the group's performances. Owen also helped establish the Posey County Agricultural Society and, in 1834, became director of the State Bank of Indiana, Evansville Branch. He died in New Harmony in 1842.Historic structures

More than 30 structures from the Harmonist and Owenite utopian communities remain as part of theNew Harmony Historic District

The New Harmony Historic District is a National Historic Landmark District in New Harmony, Indiana. It received its landmark designation in 1965, and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, with a boundary increase in 20 ...

, which is a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

. In addition, architect Richard Meier

Richard Meier (born October 12, 1934) is an American abstract artist and architect, whose geometric designs make prominent use of the color white. A winner of the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1984, Meier has designed several iconic buildings ...

designed New Harmony's Atheneum

New Harmony's Atheneum is the visitor center for New Harmony, Indiana. It is named for the Greek Athenaion, which was a temple dedicated to Athena in ancient Greece. Funded by the Indianapolis Lilly Endowment in 1976, with the help of the Kran ...

, which serves as the Visitors Center for Historic New Harmony, and depicts the history of the community. Also listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

are the George Bentel House

George Bentel House is a historic home located at New Harmony, Posey County, Indiana, United States. It was built about 1823, and is a two-story, Harmonist brick dwelling. It has a wood shake gable roof. It is an example of the standardized, ...

, Ludwig Epple House

Ludwig Epple House is a historic home located at New Harmony, Posey County, Indiana. It was built about 1823, and is a two-story, Harmonist frame dwelling. It has a gable roof. It is an example of the standardized, mass-produced form of Rapp ...

, Harmony Way Bridge, Mattias Scholle House

Mattias Scholle House is a historic home located at New Harmony, Posey County, Indiana. It was built about 1823, and is a two-story, Harmonist brick dwelling. It has a gable roof. It is an example of the standardized, mass-produced form of Ra ...

, and Amon Clarence Thomas House

Amon Clarence Thomas House is a historic home located at New Harmony, Posey County, Indiana. It was built in 1899, and is a -story, eclectic red brick dwelling with Queen Anne, Romanesque Revival, and Classical Revival style design elements. ...

.

Geography

New Harmony is located at (38.128583, −87.934122). TheWabash River

The Wabash River ( French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows fro ...

forms the western boundary of New Harmony. It is the westernmost settlement in Indiana.

According to the 2010 census, New Harmony has a total area of , of which (or 98.46%) is land and (or 1.54%) is water.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to theKöppen Climate Classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

system, New Harmony has a humid subtropical climate

A humid subtropical climate is a zone of climate characterized by hot and humid summers, and cool to mild winters. These climates normally lie on the southeast side of all continents (except Antarctica), generally between latitudes 25° and 40° ...

, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.

Demographics

2010 census

As of thecensus

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses incl ...

of 2010, there were 789 people, 370 households, and 194 families residing in the town. The population density

Population density (in agriculture: standing stock or plant density) is a measurement of population per unit land area. It is mostly applied to humans, but sometimes to other living organisms too. It is a key geographical term.Matt RosenberPopul ...

was . There were 464 dwelling units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the town was 99.0% White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

, 0.3% Native American, 0.1% Asian

Asian may refer to:

* Items from or related to the continent of Asia:

** Asian people, people in or descending from Asia

** Asian culture, the culture of the people from Asia

** Asian cuisine, food based on the style of food of the people from Asi ...

, and 0.6% from two or more races.

There were 370 households, of which 17.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.7% were married couples

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between t ...

living together, 7.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 2.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 47.6% were non-families. 43.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 23.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.93 and the average family size was 2.62.

The median age in the town was 55.1 years. 13.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.7% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 17.3% were from 25 to 44; 30.4% were from 45 to 64; and 33.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the town was 43.2% male and 56.8% female.

2000 census

As of the 2000census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses incl ...

, there were 916 people, 382 households, and 228 families residing in the town. The population density was . There were 432 dwelling units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the town was 98.91% White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

, 0.55% Native American, 0.22% Asian

Asian may refer to:

* Items from or related to the continent of Asia:

** Asian people, people in or descending from Asia

** Asian culture, the culture of the people from Asia

** Asian cuisine, food based on the style of food of the people from Asi ...

, and 0.33% from two or more races. Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to Vic ...

or Latino

Latino or Latinos most often refers to:

* Latino (demonym), a term used in the United States for people with cultural ties to Latin America

* Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States

* The people or cultures of Latin America;

** Latin A ...

of any race were 0.44% of the population.

There were 382 households, out of which 27.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.9% were married couples

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between t ...

living together, 9.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.1% were non-families. 38.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 21.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.12 and the average family size was 2.80.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 20.3% under the age of 18, 4.5% from 18 to 24, 21.2% from 25 to 44, 24.7% from 45 to 64, and 29.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 47 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 71.4 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $28,182, and the median income for a family was $40,865. Males had a median income of $39,250 versus $21,607 for females. The per capita income

Per capita income (PCI) or total income measures the average income earned per person in a given area (city, region, country, etc.) in a specified year. It is calculated by dividing the area's total income by its total population.

Per capita i ...

for the town was $17,349. About 12.2% of families and 12.4% of the population were below the poverty line

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for t ...

, including 14.8% of those under age 18 and 17.1% of those age 65 or over.

Paul Tillich Park

Paul Tillich Park commemorates the renowned twentieth century theologian,Paul Johannes Tillich

Paul Johannes Tillich (August 20, 1886 – October 22, 1965) was a German-American Christian existentialist philosopher, religious socialist, and Lutheran Protestant theologian who is widely regarded as one of the most influential theolog ...

. The park was dedicated on 2 June 1963, and Tillich's ashes were interred there in 1965.

Located just across North Main Street from the Roofless Church, the park consists of a stand of evergreens on elevated ground surrounding a walkway. Along the walkway there are several large stones on which are inscribed quotations from Tillich's writings. James Rosati

James Rosati (1911 in Washington, Pennsylvania 1911 – 1988 in New York City) was an American abstract sculptor. He is best known for creating an outdoor sculpture in New York: a stainless steel ''Ideogram.''

Life

Born near Pittsburgh, R ...

's sculpture of Tillich's head rises at the north end of the walkway, backed by a clearing and a large pond.

Those who walk thTillich Park Finger Labyrinth

, which was created by Reverend Bill Ressl after an inspirational walk through the park, are also invited to ponder the quotations and discern Tillich's systematic theology.

Secondary education

For over 200 years, New Harmony was served by New Harmony School, a K–12 school. In 2012, due to low enrollment and funding cuts, the school consolidated with the MSD of North Posey County which operates four schools: *North Posey High School

North Posey Senior High School is a public high school located in Poseyville, Indiana. North Posey is the high school for the MSD of North Posey County, which includes Bethel, Robb, Smith, Harmony, Center and Robinson Townships in Posey County, ...

(9–12)

*North Posey Junior High School (7–8)

*North Elementary School (K–6)

*South Terrace Elementary School (K–6)

Highways

*Indiana State Road 66

State Road 66 is an east–west highway in six counties in the southernmost portion of the U.S. state of Indiana.

Route description

State Road 66 begins at the eastern end of a toll bridge over the Wabash River in New Harmony and ends at U. ...

, ends at New Harmony Toll Bridge

The New Harmony Toll Bridge, also known as the Harmony Way Bridge, is a now-closed two-lane bridge across the Wabash River that connects Illinois Route 14 with Indiana State Road 66, which is Church Street in New Harmony, Indiana. The bridge l ...

.

* Indiana State Road 68

State Road 68 in the U.S. State of Indiana is a route in Gibson, Posey, Spencer and Warrick counties.

Route description

State Road 68 begins in New Harmony at State Road 69 and runs east, passing through the towns of Poseyville, Cynthiana, ...

, ends just north of New Harmony

* Indiana State Road 69

State Road 69 (SR 69) is a part of the Indiana State Road system that runs between Hovey Lake Fish and Wildlife Area and Griffin in US state of Indiana. The of SR 69 that lie within Indiana serve as a major conduit. Some of the high ...

, used to end at New Harmony, now goes around town and ends at nearby Griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (Ancient Greek: , ''gryps''; Classical Latin: ''grȳps'' or ''grȳpus''; Late Latin, Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a legendary creature with the body, tail ...

.

Arts

* New Harmony is the setting for the season three finale ofThe CW

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

television series ''Supernatural

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin (above, beyond, or outside of) + (nature) Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings si ...

''.

*A short experimental film''The Ends of Utopia''

was created in 2009 by a Vanderbilt University student.

See also

*Ambridge, Pennsylvania

Ambridge is a borough in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, United States. Incorporated in 1905 as a company town by the American Bridge Company, Ambridge is located 16 miles (25 km) northwest of Pittsburgh, along the Ohio River. The population was ...

* Grand Rapids Dam

The Grand Rapids Dam was a dam located on the Wabash River on the state line between Wabash County and Knox County in the U.S. states of Illinois and Indiana. The dam was built in the late 1890s by the Army Corps of Engineers to improve navigat ...

* Grand Rapids Hotel

The Grand Rapids Hotel also known as The Grand Rapids Resort, was a hotel that existed outside of Mount Carmel, Illinois, in Wabash County, Illinois, United States in Southern Illinois from 1922 to 1929. The hotel was located on the Wabash River ...

* Harmony Society